Malcolm Gladwell suggested it takes 10,000 hours of practice to achieve mastery of complex skills and materials, like playing the violin or getting good at programming. My father would often correct me and tell me practice does not make perfect, perfect practice makes perfect.

Others, such as David Epstein, would argue, that mastery comes from a prolonged sampling period of many different kinds of things in wicked learning environments.

While discussions on how one achieves mastery continues to be debated, I’ve wanted to give a talk at GDC since I attended my first GDC back in 2015. Now that I have spent the last six years in game dev and five years in production (around 10,000 hours) with four different companies, I feel like my collective learning would be useful to share to ensure that others can learn from my mistakes.

- Know Your Audience

One thing I learned rather quickly and continue to learn is knowing who you’re talking to and understanding how best to get information to them in a way they can understand. One way to think like this is in “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People“, where one of its crucial habits is to “Seek First to Understand, Then to Be Understood”. Some people call this empathetic listening, which Philip Crownley defines as “getting inside another person’s frame of reference, with the intent of true understanding. Seeing the world the way other people see it allows us to understand how they feel.”

Now this lesson is crucial because its widely applicable. Are you boots on the ground developing a feature for your next release? Are you pitching to a publisher for funding? Are you writing a risk assessment to upper management to get additional resources for a feature that is almost at the finish line but needs a few more hands to get it to ship? Knowing your audience is key to knowing what information it is they need, how they need that information and if they are the ones making the call and you need to provide them with options, or if you’re making the call and needing to relaying that message to a larger team.

I have this as point one for this presentation since so many things really start and end here, without knowing who you are talking to, its hard to formulate the message in the first place.

- People Over Process

The very first piece of advice given to me by one of my first production bosses at NetherRealm, Fuzzy Gerdes, was “Figure out why the jobs I work for do the terrible things they do”.

I think being inquisitive is a core quality in many of the best producers I have worked with, and wondering how systems or process that were intended to help teams are now hurting them is something I have often thought about. You may look at a process and see it as inefficient and immediately move to make it “better” without knowing why it was made in the first place. You might correctly assume it was not well thought out and this is something you can fix, or it might be intentionally obtuse to slow things down.

For example, you might see an art asset request pipeline that is cumbersome with a long laundry list of macro fields you need to fill out in a Slack workflow before you hear back from that team’s producer several days later, and you think it would just be quicker to email or slack the producer for that team to get a JIRA made that morning. However, maybe that pipeline is the way it is in order to slow the velocity of requests down since that team had been getting so many requests non-stop, that their team was having a hard time properly tracking requests. Knowing that info could save you the headache and help get you in that team’s good graces for future requests.

- Build Your Foundations

Sometimes knowing what you are good at or what you enjoy is more important then knowing what you’re not good at or hate doing. Building on those interests either as an individual or as the core competency of a team and knowing how to stick to that can be incredibly valuable. In economics, that is called either a Absolute Advantage or Comparative Advantage, something that gives you an edge in your respective market.

In our market of game development, a few examples of good core competency building can be seen by looking at Bethesda Game Studios and NetherRealm. Both studios have a core competency (open world rpgs, fighting games) that have become their bread and butter. Both studios took some forays into genres they normally would not have done but did so because, creatively, they wanted to do something else then what they traditionally did (Elder Scrolls Adventures: Redguard, Mortal Kombat: Shaolin Monks) that while different, went against player expectations for their works. Eventually, they both were able to find other ways to vary their work creatively while sticking to their core competencies (Fallout 3, Injustice).

- Fail Fast

The best way to find the right way is to figure out the wrong way, quickly and repeatedly. There’s the Thomas Edison quote that “I have not failed, I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work” when he was trying to invent the light bulb. Failure is actually the greatest way to develop games and develop skills as a producer. Learning how to fail is important and necessary since it can teach you humility but also teach you about your own boundaries as well as how to ask others for help.

A great tool for failure is deadlines, which is one of the reasons I love them. Deadlines, while almost universally hated, are essentially the thing that forces fun ideas into playable reality. You may have deadlines imposed on you by product, publishers or other places, so empowering your teams to set their own deadlines can help ensure that what you’re aiming to deliver on is clear to them.

- Get To the Fun Quicker

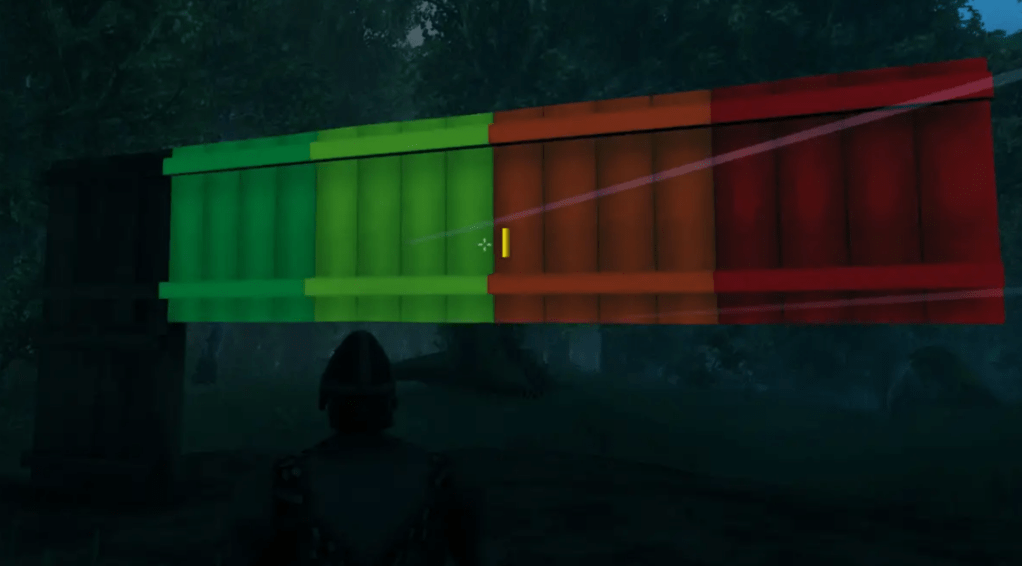

In Todd Howard’s D.I.C.E Keynote in 2011, he shared this slide which even when I first saw it in high school, it resonated with me. Making games is often thought about as creative genius that, once realized, can then be appreciated for what it is.

So often though, great games aren’t pieces of marble that your team knows exactly what they will be and will chip away at them till the image is fully there the way Michelangelo created David, sometimes you need to just get something there, play it and figure out where the fun is first. Doing this will often save you a ton of time and a ton of headaches

I’ve heard this called lots of things, from the Minimum Viable Playable (MVP) or greybox play-through but I always like to call it getting to the fun quicker, find what is fun with what you have and elevate that.

- Trust Your Team’s Instincts, Empower Them

Gut instincts land somewhere between the worlds of data and anecdote. After looking at whatever data you’re using to gauge whether you should or shouldn’t do something (player sentiment on social media, KPIs, etc) or if you’re just making decisions purely off of vibes alone, do what you can to solicit thoughts from your team. In my experience, decisions that are brought from the top down and that are specific rarely get universal buy in. Ideas that bubble up within a team though, those are the diamonds in the rough you should try and nurture.

In a creative industry, your best work always comes from things you care about, so having core gameplay pillars or studio foundations as guidelines to help guide people to the kind of work you’re looking for is key. In Patrick Plourde’s 2010 GDC Talk on The Making of Assassin’s Creed 2, everything came down to three pillars (timing based combat, fluid navigation and social stealth) and with that at its core, of its 230+ features within the game, only one or two features needed a second design pass / iteration. I like to think that a combination of clear design goals, looming deadlines and creative autonomy led to that being possible.

- Know the Difference Between Trees and Forests

Lastly, knowing where you need to be focused is usually where good games can become great games. You can call this by a couple different idioms, like Know the Difference Between Trees and Forest, or Lose the Battle to Win the War, the idea is some times you need to shift your attention to certain features or aspects of development and de-prioritize or cut others. Going back to Patrick Plourde’s The Making of Assassin’s Creed 2, there is an economic system that lacked refinement and depth compared to other features in that game since it was not attached to any of the three main design pillars for the game, so while it could have been deeper / more thought out, it was fine as it was since it was not a main focus for the game and it would not have made much sense to over design it.

And those are my seven lessons learned from 10,000 hours in game production that I’d like to impart on the next generation of video game producers or those interested in making games. If you’ve gotten this far, thanks for listening! If you ever want to talk more about game development, feel free to reach out at any of the places I inhabit online!

Leave a comment